That summer of 1999, there was precious little of the outward angst or inner turmoil so often associated with those who face an identical decision.

And, at some point, sooner or later, by choice or by circumstance, they all must.

“I guess,” reasons Jamie Macoun, over three decades later, “it’s something similar to being outside in the cold, working.

“Like, say, a construction guy.

“You’re out there all day, and you finally get finished and come in out of the cold and then – only then – do you start to realize how cold you actually are, how sore you are and how everything else you are.

“That’s how it happened for me.

“All the punishment you take and you dish out adds up.

“You stop working out the way you had been and all these bruises, bangs, sore spots, that I’d accumulated over time came to the surface.

“I’d say it really was about a year, a year and half before I started feel good again. Felt normal. Before I’d wake up in the morning and say: ‘Oh, my knees aren’t sore anymore.’ Or: ‘My shoulders feel better.’

“All those little things.

“Meaning the simple answer is: I was happy to retire. “I was turning 39 that summer.

“I was kinda my own agent at the time and didn’t put any feelers out, didn’t even ask any other teams. I mean if, say, Cliff Fletcher had called me up and said: ‘Hey, Jamie, we’ve got a spot for you’ I probably would’ve gone.

“But I didn’t go looking for it.

“I’d put a long shift in.”

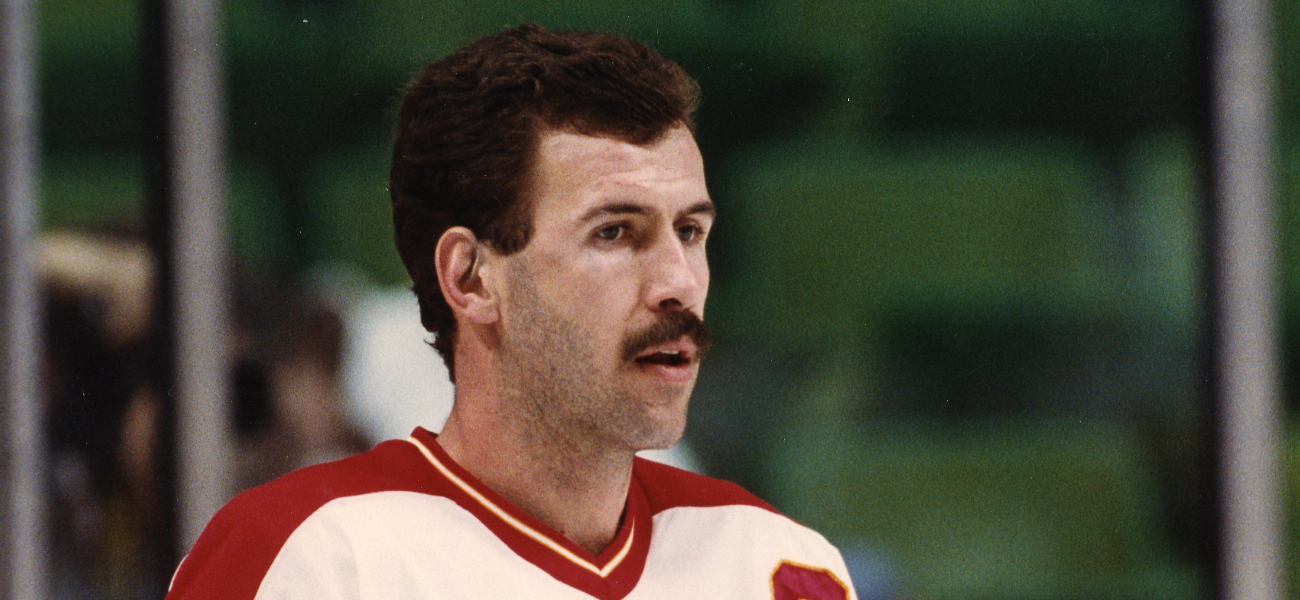

Long, yes. And quietly distinguished, too. Over 1,300 top-flight games. Two Stanley Cup rings to show. Tutored by some illustrious coaches, among them Badger Bob Johnson, Pat Burns and Scotty Bowman. A pair of World Championship silver medals and the Directorate Award as top defenceman of the 1991 tournament in Finland.

A resume that would be the envy of most.

All of this as an undrafted, rock-solid, not-to-be-trifled-with defenceman out of the Ohio State Buckeyes’ hockey program; who’d dropped out of school to sign a pro contract with the Calgary Flames in January of 1983.

At the time he could’ve had absolutely no inkling of where the game would steer him.

So when the end did, in fact, arrive, he took a good, solid, year off, puttered around the house, hung out with the kids, played some golf.

Decompressed. Healed up.

“Then,” Macoun admits, “you start getting the itch. You’re still young. Forty-one, in my case. I started working in the oil patch a little bit, learning that. It’s obviously interesting to learn more things.”

The economics of the game.

“When I was playing, salaries were good – don’t get me wrong – but nowhere near where they are today,” he reminds you. “If you’re lucky enough to play three, four good years in the NHL now, you could retire. Comfortably.

“When I was playing, going back to my days with guys like Pat Ribble, Eddy Beers, Jimmy Jackson – I’m thinking of guys who played but didn’t enjoy 15-year careers – and didn’t make any big money, things were different.

“I think it was Guy Chouinard who said to me: ‘If you can buy a house and have it paid for before you retire, you are, like, a king.’ Compared to your high-school friends.

“So that was the goal. That was the key.”

The transitory nature of hockey had taken some getting used to (Macoun would discover that first-hand on Jan. 2, 1992, as part of the infamous 10-player mega-swap involving the Flames and Toronto Maple Leafs).

“I remember early on, one summer, being in school (after he’d signed with the Flames) and getting a phone call from someone saying: ‘Hey, we just traded this person and that person.’ And I’m like: Whoa! How’d that happen?’ Four or five guys, moving this way and that.

“Right there, it struck me – this is a business. As much fun as it is, as exciting as it is, you’re a commodity.

One moment you’re somewhere, the next, you’re not.

“So I was always looking for an escape route.”

In search of that elusive fall-back escape route, Macoun had ventured into a real estate partnership franchise here back in the late ’80s, for Re/Max, staying with that venture for almost a decade.

Five or six years following the trade to Toronto and unsure where he’d finally settle, Macoun sold his interest to his partner.

These days he’s returned to those business roots, running Macoun Real Estate for Re/Max, as well as having a long-standing part-ownership in a automobile dealership in Orangeville, Ontario, Blackstock Ford Lincoln.

“That,” he says of the dealership, “is kind of like my RSP, right?”

Macoun also acts as president of the Calgary Flames Alumni Association.

“I’ve been doing the real estate again for eight years now,” he says. “I enjoy it. I like meeting people. I like helping people out.

“As much as we realize that most people buy houses it’s a daunting task for a lot of them, when they’ve never bought before, or haven’t for, say, 20 years and the rules and the pricing have changed.

“To help someone in that transition from small house to larger house, or vice versa, gives you satisfaction.

“It can be a tough business. You sell a house in a timely manner and they think they’ve overpaid. But if it takes four months to sell, you’re not doing a good job.

“I’m not sure of the numbers now but for a lot of years about 20 per cent of the realtors would transition out.”

There can be the odd over- customer.

“I’ll show some people 40 houses. Forty. And they’re undecided. I call it the Kardashian Effect,” Macoun says. “People see these places – palaces, I guess you’d call them – on TV all the time and they say to me: ‘Oh, I need to have a 2,000-square-foot ensuite, too.’ And I’m like: ‘Well, ooooooooookay. There’s a house right here – for $7 million. That’s how you get a 2,000-square-foot ensuite.’

“And their eyes pop.

“People always keep thinking there’s something better, something better, something better. But by the time they realize that’s it, the one you showed them that actually works for them has been sold. And they say: ‘Sold? It’s sold?!! You didn’t tell me!’ And I’m like: ‘Well, yes, I did tell you.’

“All in all, though, there are people built not just for real estate but meeting people, talking to people, putting them at their ease, hopefully.

“I’d like to believe I’m one of those people.

“But every client’s a new test. You can do 99 good ones in a row and then run into one that you just don’t mesh with.

“And hopefully you don’t do too much damage, right?”